Dear HHS/CDC:

Please stop saying that ebola is only transmitted through direct contact with body fluids of an infected person - and that ebola is not airborne. This is not entirely accurate.

Ebola can be spread via the air depending on proximity and droplet size.

At FluTrackers we have been talking about this for months.

Thanks, and a couple of blogs by two members, below, that convey our opinions on this matter (my bolding in red):

It's what falls out of the aerosol that matters....

What's in an aerosol?

What's in an aerosol?

Here we're talking about a mixture of different sized stuff. Think of the size range in a handful the sand from a shelly beach.

A cough/sneeze includes big, wet, heavy propelled droplets that quickly fall to the ground or hit your windscreen (hate it when that happens) or your friend's face (they hate it when that happens) down to dried or gel-like "droplet nuclei" that can float in the air for hours, travelling where the wind blows them; and every size in between.

I've also talked about this before, here.

Posted by Ian M Mackay

---------------------------------------------

Monday, August 11, 2014

Ebola: Parsing The CDC’s Low Risk vs High Risk Exposures

# 8940

Five days ago (Aug 7th) the CDC released a revisedCase Definition for Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) which I covered here. As has been pointed out before, case definitions and other guidance documents are based on the CDC’s current understanding of a particular pathogen – but they not static – and they can be expected to evolve as more is learned about any given threat.

While these risks may be considered low, they are not zero, and so it is important that people understand them. Still, to be infectious, a person has to be both infected, and symptomatic. And the odds of being exposed to someone outside of the `hot zones’ in West Africa right now are very slim.

Please stop saying that ebola is only transmitted through direct contact with body fluids of an infected person - and that ebola is not airborne. This is not entirely accurate.

Ebola can be spread via the air depending on proximity and droplet size.

At FluTrackers we have been talking about this for months.

Thanks, and a couple of blogs by two members, below, that convey our opinions on this matter (my bolding in red):

It's what falls out of the aerosol that matters....

v2 031014

"Aerosol" is a messy word. It means different things to different people. So does "airborne".

What's in an aerosol?

What's in an aerosol?Here we're talking about a mixture of different sized stuff. Think of the size range in a handful the sand from a shelly beach.

A cough/sneeze includes big, wet, heavy propelled droplets that quickly fall to the ground or hit your windscreen (hate it when that happens) or your friend's face (they hate it when that happens) down to dried or gel-like "droplet nuclei" that can float in the air for hours, travelling where the wind blows them; and every size in between.

I've also talked about this before, here.

The public rightly get confused about aerosols. And science and physics and medicine have their own defined meanings - sometimes at odds with each other - that may well be out of step with what the public think.

I do wish the the big public health entities would settle on some definitions for these and other words. It would make everyone's life a lot easier.

Direct contact.

When we talk about "direct contact" and Ebola virus transmission, we do include the bigger wetter heavier droplets that might be propelled from of a sick person during vomiting, or coughing as a risk for transmitting virus.

Even though that is not physical direct contact, and even though the droplets travel across a gap between people - through the air - it is still a direct line from person A (red in the graphic below) to B (blue). If B is too far away, then those droplets fall to the ground before they hit B. The droplets may remain infectious on the ground. That depends on temperature, humidity, surface type and the type and amount of virus.

The airborne route.

Even though it involves a short period of travel through the air, coughing wet droplets directly onto someone's mucous membranes is not an airborne thing. The term "airborne" is reserved for floaty clouds of droplet nuclei. In humans droplet nuclei have not, to the very best of our knowledge and observations and tests, been found to contain doses of Ebola virus that cause disease in humans. Too little virus coughed into the cloud perhaps or too little that survives..it's not known why, but it is pretty clear that in households where a case of Ebola virus disease was residing, only those household members who had direct contact developed disease, and those that breathed the same air but did not have direct contact, did not develop disease.

While Ebola viruses may be present in floaty clouds of droplet nuclei, or forced to be in a floaty clouds of droplet nuclei under lab conditions with lab viruses at lab virus concentrations, a floaty cloud of droplet nuclei has not been shown to act as a source of acquisition for Ebola virus and resulting disease among humans. Sorry, did I just repeat myself?

Rest in peace.

Please don't say Reston ebolavirus or the Hot Zone. That (by all accounts riveting) book was not a scientific work, it is a dramatized work and the language is colourful and emotive and scary. The Reston ebolavirus event in non-human primates was never proven to be airborne.

Lastly and most recently, an airborne route was not found to play any role in causing disease or infection when Ebola virus infected and uninfected non-human primates were caged near each other. I've written about this and other non-human primate studies here.

To summarize.

Healthcare workers wear face protection(masks and goggles) to prevent their eyes and mouth being hit by wet droplets of virus-laden body fluids while they are in close contact with ill Ebola virus diseases patients. The also wear all-over gowns so that they don't have to sterilize their clothes between each room they move between. Use of protective equipment doesn't need to convey confusing messages about the type of route Ebola virus uses to spread but it's just lacking in enough public discussion via forums the public attend/view. Knowledge is a bit like vaccination - when coverage reaches a certain level, the community is safe (or it's understanding is complete anyway).

And why wouldn't healthcare workers protect themselves from ill patient fluids-however they come into contact with them? For a healthcare worker, body fluids from ill people they are in close and often prolonged contact with, should generally be considered infectious. This is the case whether we're talking about Ebola virus disease, HIV, measles, influenza or something else. Some of those are caused by airborne viruses, some, like Ebola virus and HIV, not.

Below is my latest attempt at trying to make all those words into a picture.

If you have ways that can help me make this even simpler - please pass them along (thanks @chrisfharvey).

Posted by Ian M Mackay

---------------------------------------------

Monday, August 11, 2014

Ebola: Parsing The CDC’s Low Risk vs High Risk Exposures

# 8940

Five days ago (Aug 7th) the CDC released a revisedCase Definition for Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) which I covered here. As has been pointed out before, case definitions and other guidance documents are based on the CDC’s current understanding of a particular pathogen – but they not static – and they can be expected to evolve as more is learned about any given threat.

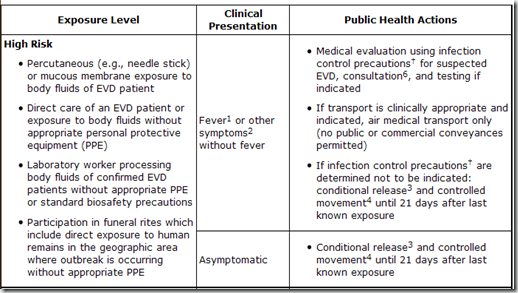

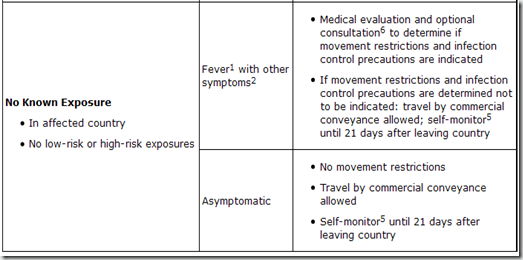

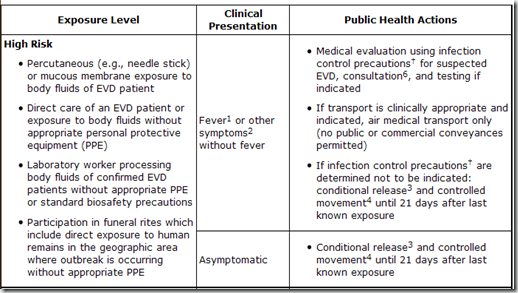

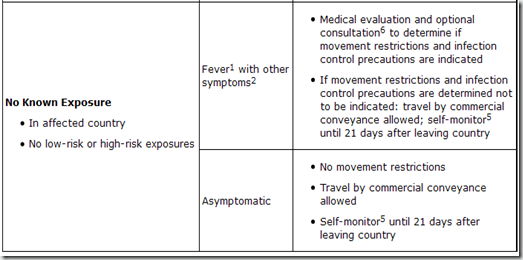

In this latest guidance, the CDC set forth three categories of potential exposure; High Risk, Low Risk, and No Known Exposures.

The High Risk exposures are the ones we have all heard about time and again: High risk exposures

A high risk exposure includes any of the following:

The CDC also listed Low Risk exposures, and over the past day or so have caused quite a stir on the Internet, with charges that this is some kind of `admission’ that Ebola is an airborne virus. A high risk exposure includes any of the following:

- Percutaneous, e.g. the needle stick, or mucous membrane exposure to body fluids of EVD patient

- Direct care or exposure to body fluids of an EVD patient without appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE)

- Laboratory worker processing body fluids of confirmed EVD patients without appropriate PPE or standard biosafety precautions

- Participation in funeral rites which include direct exposure to human remains in the geographic area where outbreak is occurring without appropriate PPE

It isn’t, but that hardly matters if your primary goal is to drive web traffic.

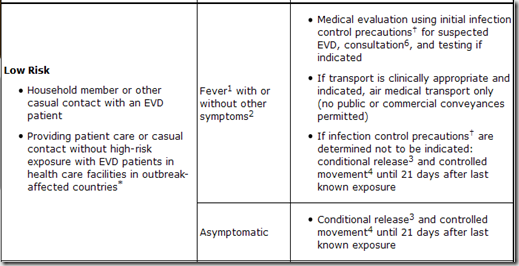

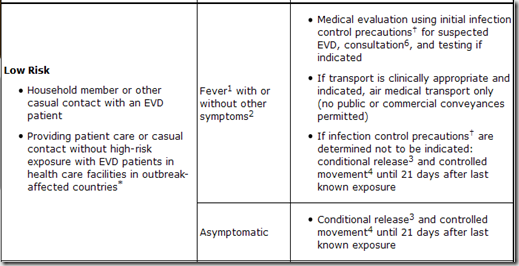

First, let’s look what the CDC considers to be Low Risk exposure: A low risk exposure includes any of the following

The term `casual contact’ is defined as: - Household member or other casual contact<sup>1</sup> with an EVD patient

- Providing patient care or casual contact<sup>1</sup> without high-risk exposure with EVD patients in health care facilities in EVD outbreak affected countries<sup>*</sup>

a) being within approximately 3 feet (1 meter) or within the room or care area for a prolonged period of time (e.g., healthcare personnel, household members) while not wearing recommended personal protective equipment (i.e., droplet and contact precautions–see Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations); or

b) having direct brief contact (e.g., shaking hands) with an EVD case while not wearing recommended personal protective equipment (i.e., droplet and contact precautions–see Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations).

At this time, brief interactions, such as walking by a person or moving through a hospital, do not constitute casual contact.

For the record, airborne viruses transmit well beyond a 1 meter radius of a patient. This 1 meter zone is basically within `spittle range’, where large droplets of mucus, blood, sweat, or other bodily fluids could potentially be coughed, sneezed, or otherwise propelled or flung onto another person. b) having direct brief contact (e.g., shaking hands) with an EVD case while not wearing recommended personal protective equipment (i.e., droplet and contact precautions–see Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations).

At this time, brief interactions, such as walking by a person or moving through a hospital, do not constitute casual contact.

While these risks may be considered low, they are not zero, and so it is important that people understand them. Still, to be infectious, a person has to be both infected, and symptomatic. And the odds of being exposed to someone outside of the `hot zones’ in West Africa right now are very slim.

There is actually another type of transmission, not really addressed here, and that is through fomites - surfaces or objects that an infected person might contaminate with body fluids - that could later infect someone else.

The trouble with including fomite exposure as an exposure risk is - unless you knew you’d been in a room with an Ebola patient (already covered above under Low risk) - you’d have no reason to suspect you’d touched a contaminated surface. While I took exception to what I considered to be an overly simplistic infographic last week on Ebola transmission risks (see The Ebola Sound Bite & The Fury), I consider these guidelines – based on what we currently know about the Ebola virus – to be quite reasonable.

As far as what should be done about people who fall into either High Risk or Low Risk Exposure groups, the CDC has released the following tables in a document called Interim Guidance for Monitoring and Movement of Persons with Ebola Virus Disease Exposure.

<sup>*</sup> Outbreak-affected countries include Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone as of August 4, 2014

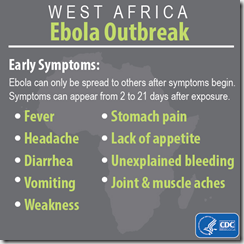

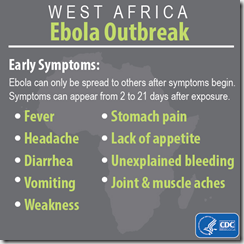

<sup>1</sup> Fever: measured temperature ≥ 38.6°C/ 101.5°F or subjective history of fever

<sup>2</sup> Other symptoms: includes headache, joint and muscle aches, abdominal pain, weakness, diarrhea, vomiting, stomach pain, lack of appetite, rash, red eyes, hiccups, cough, chest pain, difficulty breathing, difficulty swallowing, bleeding inside and outside of the body. Laboratory abnormalities include thrombocytopenia (≤150,000 /µL) and elevated transaminases.

<sup>3</sup> Conditional release: Monitoring by public health authority; twice-daily self-monitoring for fever; notify public health authority if fever or other symptoms develop

<sup>4</sup> Controlled movement: Notification of public health authority; no travel by commercial conveyances (airplane, ship, and train), local travel for asymptomatic individuals (e.g. taxi, bus) should be assessed in consultation with local public health authorities; timely access to appropriate medical care if symptoms develop

<sup>5</sup> Self-monitor: Check temperature and monitor for other symptoms

<sup>6</sup> Consultation: Evaluation of patient's travel history, symptoms, and clinical signs in conjunction with public health authority

Posted by Michael Coston at <a class="timestamp-link" href="http://afludiary.blogspot.com/2014/08/ebola-parsing-cdcs-low-risk-vs-high.html" rel="bookmark" title="permanent link"><abbr class="published" itemprop="datePublished" title="2014-08-11T13:36:00-04:00">1:36 PM</abbr>

<sup>1</sup> Fever: measured temperature ≥ 38.6°C/ 101.5°F or subjective history of fever

<sup>2</sup> Other symptoms: includes headache, joint and muscle aches, abdominal pain, weakness, diarrhea, vomiting, stomach pain, lack of appetite, rash, red eyes, hiccups, cough, chest pain, difficulty breathing, difficulty swallowing, bleeding inside and outside of the body. Laboratory abnormalities include thrombocytopenia (≤150,000 /µL) and elevated transaminases.

<sup>3</sup> Conditional release: Monitoring by public health authority; twice-daily self-monitoring for fever; notify public health authority if fever or other symptoms develop

<sup>4</sup> Controlled movement: Notification of public health authority; no travel by commercial conveyances (airplane, ship, and train), local travel for asymptomatic individuals (e.g. taxi, bus) should be assessed in consultation with local public health authorities; timely access to appropriate medical care if symptoms develop

<sup>5</sup> Self-monitor: Check temperature and monitor for other symptoms

<sup>6</sup> Consultation: Evaluation of patient's travel history, symptoms, and clinical signs in conjunction with public health authority

Comment